If factually incorrect information is presented to the children, it could be for a number of reasons. It could be because the teacher has made a genuine mistake or because science knowledge has moved on, and the teacher was not aware of new knowledge. It could be because information in a textbook is incorrect or because the instructions in the syllabus are incorrect.

If there is factually incorrect science being taught to pupils, should we start to discuss the issue of blame? For example, if the teacher is not aware that science has moved on since their lessons were planned, whose fault is that? The Local Education Authority, the school’s Senior Management Team or Board of Governors—should it be their responsibility to account for their staff’s knowledge? Should it be mandatory for teachers to keep up-to-date with the latest scientific research? How should they go about doing this? And who is going to assess what they have achieved in this area?

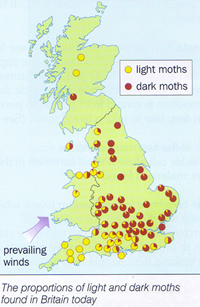

The A-Level biology textbook includes a map of the UK, showing the distribution of peppered moths of light and dark varieties. The textbook does not comment on the observation that there is a high concentration of dark-variety moths in rural East Anglia—a result which flies in the face of the usual interpretation of the observed data. Conversely, dark moths are rare in South Wales, even though this was an area of high pollution when the research was carried out.

Truth and Lies in the Classroom

If it is true that not all science teachers can keep up-to-date with the latest scientific research, how much less likely is it that ordinary parents know what errors their children are being taught? It may be an eye-opener to many parents to see which popular “icons” of scientific theories are known to be incorrect and yet are still taught as fact.

In a short article such as this, it is impossible to list all the various errors taught in the classroom; so as a case study, we will examine just one such educational error—the case of the peppered moths.

Peppered Moths

Peppered moths are usually taught as an example of natural selection. Sometimes, this is expanded to identify the moths as an example of evolution in practice. The UK’s most famous television network, the BBC takes the latter view, using peppered moths on their “GCSE Bitesize” website.1 This website provides revision assistance for children sitting General Certificate of Secondary Education exams.

The alleged support for natural selection given by peppered moths is aptly described in one current GCSE biology textbook.

“The common form is speckled but there is also a variety which is black. The black variety was rare in 1850, but by 1895 in the Manchester area its numbers had risen to 98% of the population of peppered moths. Observation showed that the light variety was concealed better than the dark variety when they rested on tree-trunks covered with lichens. In the Manchester area, pollution had caused the death of the lichens and the darkening of the tree-trunks with soot. In this industrial area the dark variety was the better camouflaged (hidden) of the two and was not picked off so often by birds.”2

It should be noticed that Mackean describes this as an example of natural selection, whereas the BBC claims it is an example of evolution. Mackean is correct.

If these experiments were genuine, they would imply a reduction in genetic information, not an increase, which is required by evolution.

What we now find is that science textbooks and syllabi are basing their evidence for evolution on something that has been a known fraud for twenty years.

Using the language of evolution, a recent A-Level biology textbook says, “Clearly the darker moth has a selective advantage over the light moth in industrial areas, whereas in non-polluted areas this advantage is with the light moth.”3 The same A-Level textbook includes a map of the UK, showing the distribution of peppered moths of light and dark varieties.

In his textbook, Williams does not comment on the observation that there is a high concentration of dark-variety moths in rural East Anglia—a result which flies in the face of the usual interpretation of the observed data. Conversely, dark moths are rare in South Wales, even though this was an area of high pollution when the research was carried out.

The alleged principles shown by peppered moths are considered educationally very important. They are included as examples in many GCSE science and biology syllabi. One current GCSE biology syllabus states: “Candidates should be able to … describe how the process of natural selection may result in … changes within a species, as illustrated by the peppered moth [emphasis added].”4

The observations about peppered moths were carried out initially in the 1950s by Bernard Kettlewell. Unfortunately, his observations should carry a “healthwarning!” Peppered moths do not, as a rule, rest on the trunks of trees; so the main premise of the experiment is flawed.

The famous photographs, used in so many textbooks, are fraudulent. Some photos were taken using dead moths glued or pinned to the trunks while others used live specimens which were placed by hand on the trunks. In daylight moths are drowsy and tend to stay where they are put. The moths actually tend to rest hidden under the leaf canopy, rather than on the trunk in the open.

It also turns out that the famous photographs, used in so many textbooks, are fraudulent. Some photos were taken using dead moths glued or pinned to the trunks while others used live specimens which were placed by hand on the trunks. In daylight moths are drowsy and tend to stay where they are put. The moths actually tend to rest hidden under the leaf canopy, rather than on the trunk in the open.

Criticisms of Kettlewell’s experiments first emerged in the 1980s—some twenty years ago. In 1998 Professor Jerry Coyne of the University of Chicago said that finding out the moth story was wrong was like when he found out at age six that it was actually his father who was bringing the Christmas presents.5 Coyne has not been pleased that his remarks have been quoted by creationists, such as this author, but the genie is out.

Kettlewell said that if Darwin had seen his experiments “he would have witnessed the consummation and confirmation of his life’s work.”6 What we now find is that science textbooks and syllabi in the UK (and, judging from my correspondence, America, too) are basing their evidence for evolution on something that has been a known fraud for twenty years.

So, what word can we use to describe the situation, if our children are knowingly being taught untruths?

Summary

It is clear from this brief analysis that children in state (government) schools, or other schools following the National Curriculum, are being taught things in their science lessons which are demonstrably untrue. These are not simply presuppositional errors—things that children might be taught because of the non-Christian or evolutionary worldview of the teacher.

In further publications, it will be instructive to analyse areas where statements in the National Curriculum or examination syllabi are influenced by such an evolutionary worldview.

Paul Taylor graduated with his B.Sc. in chemistry from Nottingham University and his masters in science education from Cardiff University. Paul taught science for 17 years in a state school but is now a proficient writer and speaker for Answers in Genesis–UK. http://www.answersingenesis.org/articles/am/v1/n1/examination-of-error