At a Glance

- Abraham Lincoln and Charles Darwin were born on the same day: February 12, 1809.

- Newsweek’s Malcolm Jones examines and compares the two men, selecting Lincoln as the more influential because of his irreplacability.

- The legacies of the two men remind us of how one’s views on the past shape one’s views of the future and one’s actions in the present.

One was a self-made American politico who freed the slaves; the other was a silver-spooned British naturalist who observed finches. So what’s the connection?

There are many possible comparisons in the annals of history that seem more apt than the one drawn in the cover story of this week’s Newsweek. In “Who Was More Important: Lincoln or Darwin?” Malcolm Jones takes a look at two of the nineteenth century’s most remembered and, in many circles, respected figures: Abraham Lincoln and Charles Darwin.

The cover of Newsweek’s July 7–14, 2008, edition.

Why the comparison between these two men, and why now? Obscure as the connection may seem at first, Lincoln and Darwin were both born on February 12, 1809, a date whose bicentennial is hardly more than a half a year away. This explains not only the Newsweek article, but also one recent and one upcoming book that examine the two men.1

How similar were Lincoln and Darwin? Most of the resemblance is relatively superficial (though perhaps not so much as “they were both male”); for example, they both lost their mothers in childhood, both had strained relationships with their fathers, both had difficulty settling on a career, and both suffered from depression. The two men were also both copious note-takers who constantly revised their thoughts with pen and paper. But the most notable connection between the men, Jones writes, is that they “each touched off a revolution that changed the world”—an assertion we certainly would not dispute.

Who Had Greater Influence?

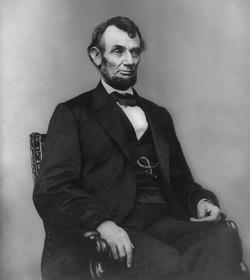

Abraham Lincoln

(February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865)

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation, so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address

As for the titular question the Newsweek article asks, it’s difficult to even envision the United States without the influence of either man. Perhaps some would hypothesize that if there were no Lincoln or no Darwin, there would nonetheless be others to take their places; but in the world of “what was” rather than “what could have been” these two men have had enormous influence in shaping modern society.

Lincoln’s most significant accomplishment, Jones explains, was defining and reasserting the very foundation of America. Centering on the Gettysburg Address, Jones writes, “[P]eople in the North were wondering aloud just what it was they were fighting for. Was it to preserve the Union, or was it to abolish slavery? Lincoln was keenly aware that he needed to clarify the issue. The Northern victory at Gettysburg in early July gave him the occasion he was seeking.”

In that short speech at Gettysburg, Lincoln reminded his audience of the democratic origin of the United States in an unvarnished, color-blind statement—“our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” This biblically based creed, that those of all “colors” are equal in God’s sight and should be treated equally by the law, became the basis for the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, which together uphold the rights of all U.S. citizens regardless of skin shade.

That achievement alone has obviously reshaped the United States extensively, though the painful effects of slavery (and segregation, which sadly continued long beyond the end of the Civil War) still manifest themselves at times in American culture. Furthermore, the very act of keeping the Union together—regardless of the controversy over slavery—helped fuel the endurance and prominence of the United States as a major world power, which in turn completely changed World Wars I and II and thus the entire twentieth century (and where we are today).

Compared to that legacy, it seems almost foolish at first to even try to compare Darwin’s influence. Academia and the educational system are obviously the prime domains of Darwin’s work, and in these areas Darwin’s influence is strong. Just as a modern United States with slavery is hardly fathomable, so too is it difficult to imagine what modern biology would be like without evolutionary doctrine. But in terms of day-to-day influence, the former clearly speaks louder than the latter. Today’s controversy over creation and evolution still pales in comparison to the controversy over slavery a century and a half ago that led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Americans.

Charles Darwin

(February 12, 1809 – April 19, 1882)

There is no fundamental difference between man and the higher mammals in their mental faculties.

from Darwin’s The Descent of Man

We could go too far, however, in emphasizing the greater influence of Lincoln; for even if one were to consider Lincoln’s war-borne rhetoric and leadership damaging, they were nonetheless overt and direct; the influence of Darwinian thought has been far more insidious, as it reshapes basic values and beliefs. Darwinism has stretched its tentacles outside the academic realm on more than one nasty occasion, but the nastiest is almost undoubtedly the Darwinism–Nazi connection (see Darwin’s impact—the bloodstained legacy of evolution and Darwinism and the Nazi race Holocaust for more on this topic). In a similar macabre connection, examine what serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer’s words say about the influence of Darwin:

“If a person doesn’t think there is a God to be accountable to, then—then what’s the point of trying to modify your behavior to keep it within acceptable ranges? That’s how I thought anyway. I always believed the theory of evolution as truth, that we all just came from the slime. When we, when we died, you know, that was it, there is nothing.

Jeffrey Dahmer, in an interview with Stone Phillips, Dateline NBC, November 29, 1994.

Darwin’s influence has definitely extended beyond academics in some unsettling ways—and, in the case of Nazi Germany, in world-changing ways. And in the church, Darwinian theory has contributed greatly to demeaning the Word of God, justifying willful ignorance of Scripture, and fueling a steady exodus of Christians into the clutches of humanism and atheism.

Malcolm Jones eventually selects Lincoln as the more influential of the two giants, justifying his pick on the grounds of Lincoln’s irreplacability relative to Darwin. Jones points out that Darwin’s contemporary Alfred Russel Wallace independently came up with the same hypothesis as Darwin but was merely beaten to the publishing punch. And both men stood on the shoulders of other naturalists—among them Darwin’s own grandfather, Erasmus Darwin—who outlined the basic idea of evolution even earlier. “In other words, there was a certain inevitability to Darwin’s theory,” Jones writes.

We would also hasten to add that Darwin’s theory would never be what it is today without the theoretical work of many other influential biologists, who effectively saved the theory from itself through modern evolutionary synthesis and ideas such as punctuated equilibria. And Darwinism would likely be dead in the water if it were not for the breakthrough discovery of genetics (which was later applied to evolutionary theory) by monk Gregor Mendel. Without a doubt, Lincoln’s achievements stand alone in a way that dwarfs Darwin’s.

What’s the Connection?

Interestingly, it seems that Darwin’s prime influence was in man’s thinking about how we got here, whereas Lincoln’s influence concerned where we were (and are) going as a society. To the casual observer, there may seem to be little connection. But recognizing the connection is key in understanding the prominence of one’s worldview. An individual’s view of the past and the future influence one another—and, consequently, influence one’s view of the present as well. And at the heart of each view are presuppositions.

For the humanist, if we originated in the amoral eons of violence and competition for scarce resources, and only later evolved both consciousness and consciences, what is the basis for establishing moral codes or laws, other than selfishness?

But the Christian recognizes our origin in Genesis, and that recognition becomes the basis for the morality we seek in our own lives and in society. For example, Genesis shows how we are all descendants of Adam and Eve through Noah, and thus how we are all of one chromatic race. This, then, gives us the basis for hoping to eradicate so-called “racist” laws and attitudes.

Ultimately, this is the joint legacy of Darwin and Lincoln: over the past 150 years, they have shown us how crucial one’s starting points are in determining what one believes about the past and about the future—and thus shaping what one does in the present.