Evidence

Doesn't Fade from Colorful Fossils by Brian Thomas, M.S. *

Evidence

Doesn't Fade from Colorful Fossils by Brian Thomas, M.S. *

Generations of onlookers have appreciated the long-lasting luster of "Egyptian blue," an ancient dye still brilliant thousands of years after it was painted onto various murals and artifacts. But a new study found colors that apparently blow Egypt's puny pigment longevity out of the water.1 Researchers discovered colorful organic chemicals embedded in fossils supposedly 340 million years old. Did the stories they concocted to explain this anomaly depart from scientific sense?

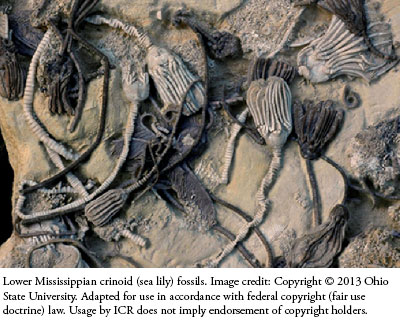

The fossils were those of crinoids, also known as sea lilies in today's oceans. But being classified as echinoderms, a group that includes sea stars, these crinoids certainly aren't flowers. Sea lilies creep across the ocean floor and use a feather-like corona, often on the end of a long stalk, to filter nutrients from water. Today's sea lilies come in blue, green, red, purple, pink, orange and yellow varieties. One is colored so brightly orange it's named the Moulin Rouge sea lily.2 Apparently, crinoids covered by sediments ages ago were arrayed in similar vivid hues.

Paleontologists

have known for years that separate species of fossil

crinoids kept their unique colors even though they had been

buried for so long, but until recently few have sought to

understand how those bright colors might have persisted

intact.

Paleontologists

have known for years that separate species of fossil

crinoids kept their unique colors even though they had been

buried for so long, but until recently few have sought to

understand how those bright colors might have persisted

intact.

Publishing in Geology, a team from The Ohio State University tested the hypothesis that the colors come from the original pigment molecules that have somehow lasted for hundreds of millions of years. The researchers used several lab techniques to help isolate and identify some general characteristics of the green, purple, orange, and yellow chemicals they extracted from the fossils.

They concluded that "organic molecules are preserved in and can be extracted from Mississippian crinoid fossils…" The fossil "molecules are a form of aromatic and/or polyaromatic quinones similar to modern echinoderm pigments."1 But how could these molecules have retained their color integrity through the ravages of so long a time?

The study authors attempted an answer. They used repeatable scientific tactics to identify the fossil's pigment chemistry, but relied on unlikely guesses to explain how those pigments lasted.

First, they asserted that these fossils must have remained dry since they were initially deposited. Nearby water flow would have dissolved, washed away, or reacted with the pigments. But how feasible is this story when considering 300 million years' worth of crustal plate collisions, catastrophic impacts, floods, earthquakes and constant weathering and erosion?3

Maybe the fossils could be protected from natural disasters and erosion if they were buried deep beneath earth's crust. But the study authors wrote that the crinoid-containing Mississippian beds from Indiana "have never been buried deeply," and therefore were not exposed to the temperatures and pressures that would metamorphose rocks and would have certainly fried the crinoid's quinones.1 In other words, the biomolecules' colors were doomed to fade if buried too deep, but doomed to spoil if held closer to the surface. The study authors did not address this dilemma.

So far, a better explanation for original chemistry remaining in these colorful fossils is that their rock layers were deposited thousands, not millions, of years ago.

References

- O'Malley, C.E., Ausich, W.I., and Y-P Chin. 2013. Isolation and characterization of the earliest taxon-specific organic molecules (Mississippian, Crinoidea). Geology. 41 (3): 347-350.

- Proisocrinus ruberrimus (Moulin Rouge). Natural History Museum fact sheet. Posted on nhm.ac.uk, accessed February 21, 2013.

- Thomas, B. Continents Should Have Eroded Long Ago. Creation Science Update. Posted on icr.org August 22, 2011, accessed February 21, 2013.

* Mr. Thomas is Science Writer at the Institute for Creation Research.