Theologians

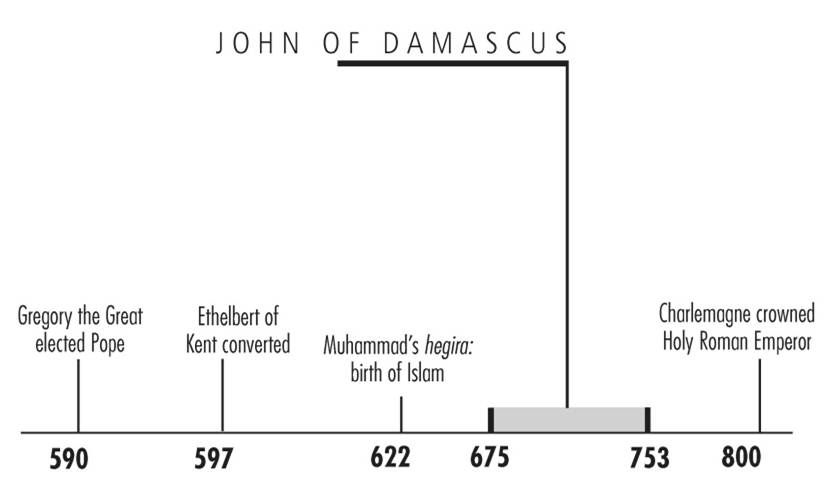

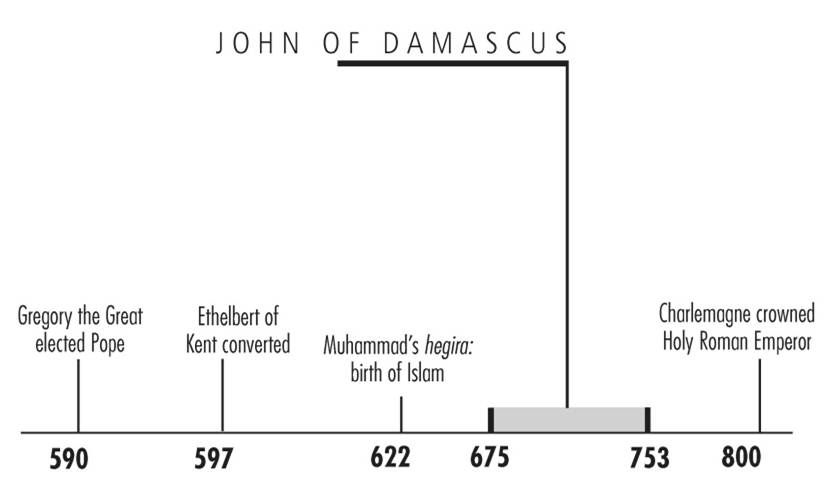

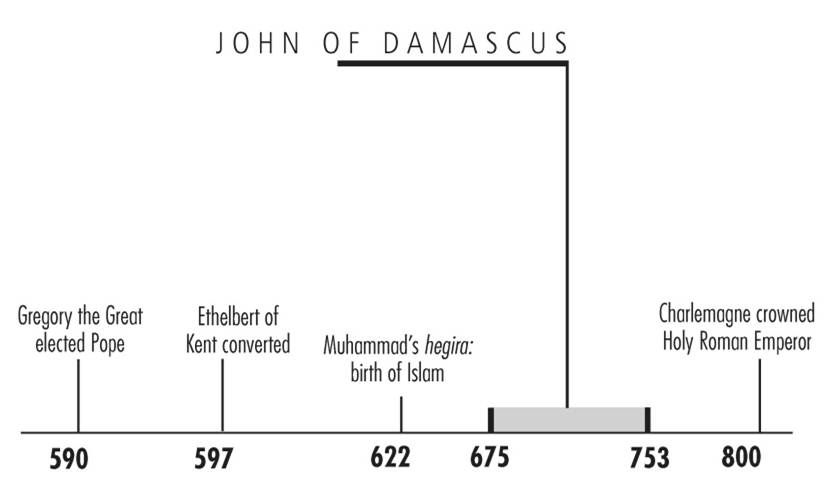

John of Damascus

Image-conscious Arab

“I do not worship matter, I worship the God of matter,

who became matter for my sake and deigned to inhabit matter, who worked out

my salvation through matter. I will not cease from honoring that matter

which works for my salvation. I venerate it, though not as God.”

Visitors to an Orthodox Church are confronted with many

unfamiliar elements of worship: for example, the use of incense and

Byzantine chant and the custom of standing throughout the service. But

perhaps the most perplexing element is the icons, especially when Orthodox

worshipers bow before and kiss them. Isn’t this idolatry?

This very question raged through the Christian world in the

eighth and ninth centuries, and it occupied the attention of two of the

seven ecumenical (worldwide) church councils. The strongest defense of the

practice came from a Christian living in the heart of the Islamic empire,

John of Damascus.

Responding to the imperial volcano

He was born John Monsur, into a wealthy Arab-Christian

family of Damascus. Like his father, he held a position high in the court of

the caliph. About 725 he resigned his office and became a monk at Mar Saba

near Bethlehem, where he became a priest. In this secluded place at the

relatively advanced age of 51, John’s lasting legacy began to unfold. It

began when Emperor Leo III, in 726, outlawed the veneration of icons.

The conflict had been brewing for decades. It wasn’t a

question of bowing and kissing icons; this was a culturally acceptable way

to show respect. The basic question went deeper: are Christians allowed to

paint pictures of Jesus, or other biblical figures, at all? As Islam spread

through the Mediterranean region, bringing its absolute interdiction of

images, Christianity was feeling pressure to rid itself of images.

The main threat to icons came not from the Islamic caliph

but from the heart of the Byzantine Empire. A few bishops from Asia Minor

(now Turkey) believed the Bible, particularly the second commandment,

forbade such images:

“You shall not make for yourself an idol in the form of

anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below. You

shall not bow down to them or worship them.”

The bishops’ argument convinced Byzantine Emperor Leo III,

who set about to convince his subjects to abandon iconography. But a natural

disaster changed his approach. In 726 a violent volcano erupted in the

middle of the Aegean Sea and terrorized Constantinople, the capital.

Afterward, tidal waves buffeted the shores and volcanic ash extinguished the

sunlight. Leo reasoned that God was angry about icons. That’s when he

outlawed their use.

In 730 Leo commanded the destruction of all religious

likenesses, whether icons, mosaics, or statues, and iconoclasts (“image

smashers” in Greek) went on a spree, demolishing nearly all icons in the

Empire.

From his distant post in the Holy Land, John challenged this

policy in three works. He argued that icons should not be worshiped, but

they could be venerated. (The distinction is crucial: a Western parallel

might be the way a favorite Bible is read, cherished, and treated with

honor—but certainly not worshiped.)

John explained it like this: “Often, doubtless, when we have

not the Lord’s passion in mind and see the image of Christ’s crucifixion,

his saving passion is brought back to remembrance, and we fall down and

worship not the material but that which is imaged: just as we do not worship

the material of which the Gospels are made, nor the material of the Cross,

but that which these typify.”

Second, John drew support from the writings of the early

fathers like Basil the Great, who wrote, “The honor paid to an icon is

transferred to its prototype.” That is, the actual icon was but a point of

departure for the expressed devotion; the recipient was in the unseen world.

Third, John claimed that, with the birth of the Son of God

in the flesh, the depiction of Christ in paint and wood demonstrated faith

in the Incarnation. Since the unseen God had become visible, there was no

blasphemy in painting visible representations of Jesus or other historical

figures. To paint an icon of him was, in fact, a profession of faith,

deniable only by a heretic!

“I do not worship matter, I worship the God of matter, who

became matter for my sake and deigned to inhabit matter, who worked out my

salvation through matter,” he wrote. “I will not cease from honoring that

matter which works for my salvation. I venerate it, though not as God.”

Eastern theologian for the whole church

While the controversy continued to rage, John spent his days

at Mar Saba monastery in the hills 18 miles southeast of Jerusalem. There he

wrote both theological treatises and hymns; he is recognized as one of the

principal hymnographers of Eastern Orthodoxy. His most important theological

work, The Fount of Wisdom,

is a summary of Eastern theology.

Tradition says that his fellow monks grumbled that such

elegant writing was a distraction and prideful; so John was sometimes sent

to sell baskets humbly in the streets of Damascus, where he had once been

among the elite.

After more dissension and bloodshed over icons (the decade

after John’s death, over 100,000 Christians were injured or killed), the

issue was finally settled, and icons are an integral part of Orthodox

worship to this day. His other writings were major influences on Western

theologians such as Thomas Aquinas. In 1890 he was named a doctor of the

church by the Vatican, and in this century, his writings have become a fresh

source of theological insight, especially for Eastern theologians.

Galli, Mark ; Olsen, Ted: 131

Christians Everyone Should Know. Nashville, TN : Broadman &

Holman Publishers, 2000, S. 24