Theologians

Martin Luther

Passionate

reformer

“At last meditating day and night, by the mercy of

God, I began to understand that the righteousness of God is that through

which the righteous live by a gift of God, namely by faith. Here I felt as

if I were entirely born again and had entered paradise itself through the

gates that had been flung open.”

In the sixteenth century, the world was divided about Martin

Luther. One Catholic thought Martin Luther was a “demon in the appearance of

a man.” Another who first questioned Luther’s theology later declared, “He

alone is right!”

In our day, nearly 500 years hence, the verdict is nearly

unanimous to the good. Both Catholics and Protestants affirm he was not only

right about a great deal, but he changed the course of Western history for

the better.

Thunderstorm conversion

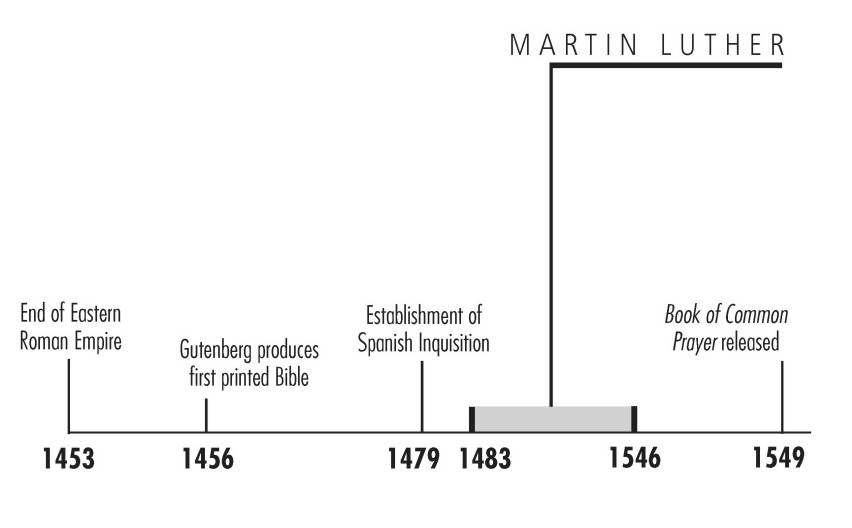

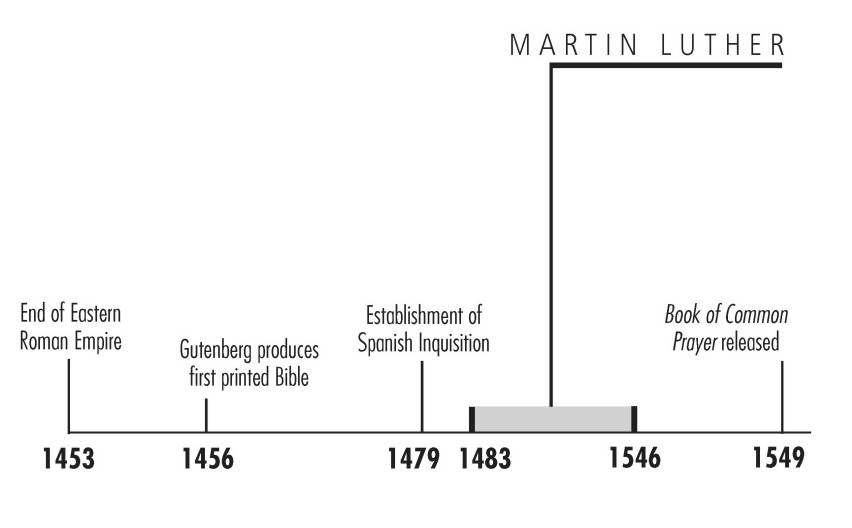

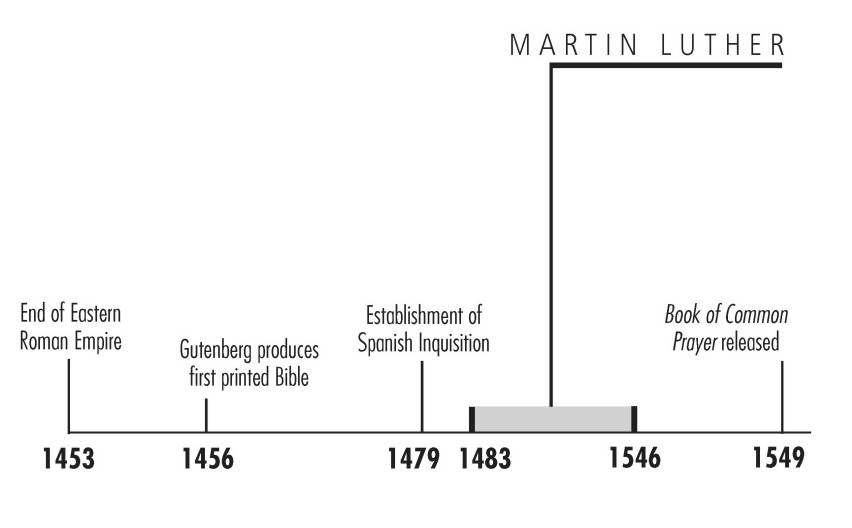

Martin was born at Eisleben (about 120 miles southwest of

modern Berlin) to Margaret and Hans Luder (as it was locally pronounced). He

was raised in Mansfeld, where his father worked at the local copper mines.

Hans sent Martin to Latin school and then, when Martin was

only 13 years old, to the University of Erfurt to study law. There Martin

earned both his baccalaureate and master’s degrees in the shortest time

allowed by university statutes. He proved so adept at public debates that he

earned the nickname “The Philosopher.”

Then in 1505 his life took a dramatic turn. As the

21-year-old Luther fought his way through a severe thunderstorm on the road

to Erfurt, a bolt of lightning struck the ground near him.

“Help me, St. Anne!” Luther screamed. “I will become a

monk!”

The scrupulous Luther fulfilled his vow: he gave away all

his possessions and entered the monastic life.

Spiritual breakthrough

Luther was extraordinarily successful as a monk. He plunged

into prayer, fasting, and ascetic practices—going without sleep, enduring

bone-chilling cold without a blanket, and flagellating himself. As he later

commented, “If anyone could have earned heaven by the life of a monk, it was

I.”

Although he sought by these means to love God fully, he

found no consolation. He was increasingly terrified of the wrath of God:

“When it is touched by this passing inundation of the eternal, the soul

feels and drinks nothing but eternal punishment.”

During his early years, whenever Luther read what would

become the famous “Reformation text”—Romans 1:17—his eyes were drawn not to

the word faith, but to the word righteous. Who, after all, could “live by

faith” but those who were already righteous? The text was clear on the

matter: “the righteous shall live by faith.”

Luther remarked, “I hated that word, ‘the righteousness of

God,’ by which I had been taught according to the custom and use of all

teachers … [that] God is righteous and punishes the unrighteous sinner.” The

young Luther could not live by faith because he was not righteous—and he

knew it.

Meanwhile, he was ordered to take his doctorate in the Bible

and become a professor at Wittenberg University. During lectures on the

Psalms (in 1513 and 1514) and a study of the Book of Romans, he began to see

a way through his dilemma. “At last meditating day and night, by the mercy

of God, I … began to understand that the righteousness of God is that

through which the righteous live by a gift of God, namely by faith.… Here I

felt as if I were entirely born again and had entered paradise itself

through the gates that had been flung open.”

On the heels of this new understanding came others. To

Luther the church was no longer the institution defined by apostolic

succession; instead it was the community of those who had been given faith.

Salvation came not by the sacraments as such but by faith. The idea that

human beings had a spark of goodness (enough to seek out God) was not a

foundation of theology but was taught only by “fools.” Humility was no

longer a virtue that earned grace but a necessary response to the gift of

grace. Faith no longer consisted of assenting to the church’s teachings but

of trusting the promises of God and the merits of Christ.

It wasn’t long before the revolution in Luther’s heart and

mind played itself out in all of Europe.

“Here I stand”

It started on All Saints’ Eve, 1517, when Luther publicly

objected to the way preacher Johann Tetzel was selling indulgences. These

were documents prepared by the church and bought by individuals either for

themselves or on behalf of the dead that would release them from punishment

due to their sins. As Tetzel preached, “Once the coin into the coffer

clings, a soul from purgatory heavenward springs!”

Luther questioned the church’s trafficking in indulgences

and called for a public debate of 95 theses he had written. Instead, his

95 Theses spread across Germany as a call to

reform, and the issue quickly became not indulgences but the authority of

the church: Did the pope have the right to issue indulgences?

Events quickly accelerated. At a public debate in Leipzig in

1519, when Luther declared that “a simple layman armed with the Scriptures”

was superior to both pope and councils without them, he was threatened with

excommunication.

Luther replied to the threat with his three most important

treatises: The Address to the Christian Nobility,

The Babylonian Captivity of the Church,

and On the Freedom of a Christian.

In the first, he argued that all Christians were priests, and he urged

rulers to take up the cause of church reform. In the second, he reduced the

seven sacraments to two (baptism and the Lord’s Supper). In the third, he

told Christians they were free from the law (especially church laws) but

bound in love to their neighbors.

In 1521 he was called to an assembly at Worms, Germany, to

appear before Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. Luther arrived prepared for

another debate; he quickly discovered it was a trial at which he was asked

to recant his views.

Luther replied, “Unless I can be instructed and convinced

with evidence from the Holy Scriptures or with open, clear, and distinct

grounds of reasoning … then I cannot and will not recant, because it is

neither safe nor wise to act against conscience.” Then he added, “Here I

stand. I can do no other. God help me! Amen.”

By the time an imperial edict calling Luther “a convicted

heretic”was issued, he had escaped to Wartburg Castle, where he hid for ten

months.

Accomplishments of a sick man

In early spring of 1522, he was able to return to Wittenberg

to lead, with the help of men like Philip Melanchthon, the fledgling reform

movement.

Over the next years, Luther entered into more disputes, many

of which divided friends and enemies. When unrest resulted in the Peasants’

War of 1524–1525, he condemned the peasants and exhorted the princes to

crush the revolt.

He married a runaway nun, Katharina von Bora, which

scandalized many. (For Luther, the shock was waking up in the morning with

“pigtails on the pillow next to me.”)

He mocked fellow reformers, especially Swiss reformer Ulrich

Zwingli, and used vulgar language in doing so.

In fact, the older he became, the more cantankerous he was.

In his later years, he said some nasty things about, among others, Jews and

popes and theological enemies, with words that are not fit to print.

Nonetheless, his lasting accomplishments also mounted: the

translation of the Bible into German (which remains a literary and biblical

hallmark); the writing of the hymn “A Mighty Fortress is Our God”; and

publishing his Larger

and Smaller Catechism,

which have guided not just Lutherans but many others since.

His later years were spent often in both illness and furious

activity (in 1531, though he was sick for six months and suffered from

exhaustion, he preached 180 sermons, wrote 15 tracts, worked on his Old

Testament translation, and took a number of trips). But in 1546, he finally

wore out.

Luther’s legacy is immense and cannot be adequately

summarized. Every Protestant Reformer—like Calvin, Zwingli, Knox, and

Cranmer—and every Protestant stream—Lutheran, Reformed, Anglican, and

Anabaptist—were inspired by Luther in one way or another. On a larger

canvas, his reform unleashed forces that ended the Middle Ages and ushered

in the modern era.

It has been said that in most libraries, books by and about

Martin Luther occupy more shelves than those concerned with any other figure

except Jesus of Nazareth. Though difficult to verify, one can understand why

it is likely to be true.

Galli, Mark ; Olsen, Ted: 131

Christians Everyone Should Know. Nashville, TN : Broadman &

Holman Publishers, 2000, S. 33