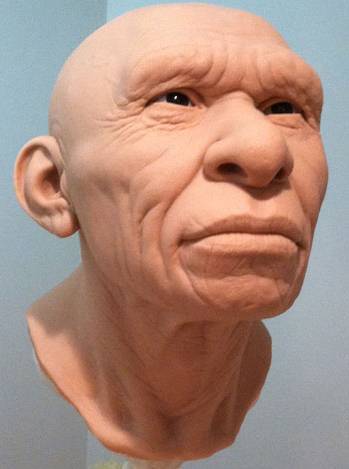

The face of Neanderthal on the cover of this issue was sculpted and designed over a plaster cast of an actual Neanderthal skull. The artist, Doug Henderson, answered a few questions about the process of turning a skull into the stunning image on the cover.

The cast of the original Neanderthal skull.

Question: You must have conducted a great deal of research before beginning the facial construction. How did you focus your research? Did you check out museums or did you focus on the work of other artists?

DH: A lot of both, actually. I looked at other artists’ recent reconstructions that I could find online and in magazines and I studied various anatomy illustrations for the general form. There really isn’t much controversy any more over the structure and form of Neanderthal. The debates seem to lie more in the details that are not captured in the fossil record, such as skin, hair, and eye color. Some reconstructions have slightly larger or smaller noses and ears, but most still seem reasonable and all of the recent reconstructions look 100% human.

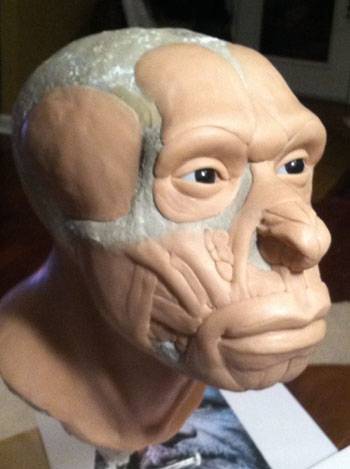

Q: How did the sculpting process work?

DH: I sculpted the head over a plaster copy of a Neanderthal skull by first building up the muscle structures with a firmer clay, then “fleshing it out” with softer clay. This way, I could easily check the tissue thicknesses by probing the clay. When I felt the resistance of the harder clay or the plaster skull I could easily double check how thick I was building up the softer tissues. Beyond that, I did a lot of research to find people who have similar facial characteristics and based the details on those references.

I used standard anatomy references to determine placement and thicknesses of muscles and cartilage.

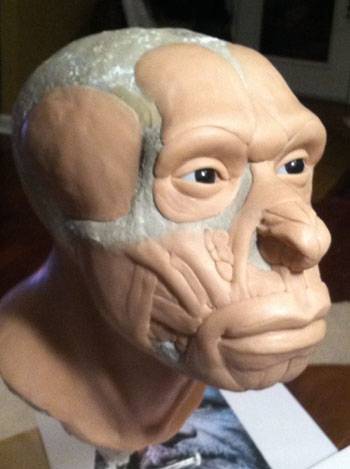

I found photos of people from around the world with similar nasal bones and based the nose on what those people’s noses had in common. The same is true for the mouth.

I applied thin sheets of clay to build up the flesh using my own flesh thicknesses as references in the bony areas.

Q: At what stage did you really begin to rely on your interpretation of the face, rather than depending on the physical evidence of the skull?

DH: Once I got past the muscle build up, I had to start thinking of how thick the fat deposits and flesh might be. I doubt this person would have been overweight, so I went with a more sinuous look. Stocky, but well-muscled. I have friends with heavy brows and their skin is much thicker in that area than mine, so I based those thicknesses of the sculpture on that. I could have easily justified making the brow flesh thicker or thinner based on references I had found, but I chose something more average.

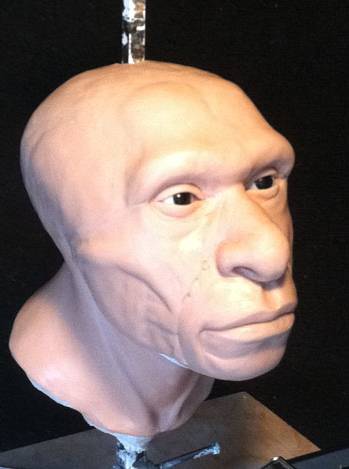

Q: What influenced your decisions while working through the soft tissues?

DH: I found references of modern people who had similar structures and harsher living conditions. People who spend most of their time living off the land and living outdoors can tend to have tougher skin. I tried to convey that with texture and coloration.

I then added ears and wrinkles and skin textures.

Q: How did you decide the hair and other window dressings (like the scar, etc.) during the graphic design phase?

DH: The dreads came up after I had made the hair initially shorter and maybe too groomed looking. The matted, organic dreadlocks made sense since dreading is a practical way of dealing with constantly growing hair, but it is simply romantic conjecture. The same is true for the scar. I wanted him to have an obvious “history” at a glance. A sort of “lived in” look. I imagined the scar was the result of a fight. I wanted it to look as if it happened a long time ago, so I illustrated it as well healed and fading.

The scar was eventually painted on in Photoshop and I used photos of another one of our artists’ (Ben Iocco) eyes in place of the doll eyes I had sculpted over. Ben’s eyes are brown, but I repainted them green and made them look older and more veiny. I also painted out the portrait light that was reflected in his eyes and replaced it with an illustration of a torch light as if he is holding one up with his left hand.

Q: Any other details in the reconstruction process you’d like to add?

DH: I am not an anatomist or forensic artist, though I have studied and used anatomy in my art over the last 20+ years. I would not consider myself to be an authority. This is simply my artistic interpretation of the skull based on reference and the experience of sculpting many human likenesses over the years.

The art of forensic reconstruction, while scientific in process, still requires imagination and interpretation and is therefore very subjective. The process of building up layers of clay at precise thicknesses to represent muscle groups is very accurate and can even be used to identify human remains. But this process is not perfect and falls short when it comes to determining the actual appearance of an extinct specimen. For example, if no one had ever seen a living skunk, but the bones were found and assembled and clay was built up to forensically reconstruct the muscles, do you think the artist would know to finish the model with medium length, dense, black fur and double white stripes down its back? How big would they make the ears? What shape would they be? Would they be able to determine from the bones that this creature could spray a foul smelling liquid to defend itself?

The answer is: probably not.

The same could be said of Neanderthals and indeed, all extinct fossil specimens.

Artists have displayed their interpretation of hominids and so-called ape men for many years, in books, magazines, movies and museums, using scientific processes where possible, and filling in the missing information with creativity, imagination, and their best guesses based on popular opinion or the opinion of the individual who hired them. As a result, whether intentional or not, the final look of the model or drawing is shaped by the biases of the artist and the scientists who direct the process. In other words, people’s starting points influence their view of the evidence, and consequently, their biases show through in their artwork, whether it is forensic or interpretive.