In 1993, a fossil of a long-tailed bird was found in China that still contained feathers and bones. The fossilized Confuciusornis sanctus is supposedly 120 million years old, but observation has shown that original organic materials such as bones and feathers break down in just thousands of years, even if bacteria aren't present.

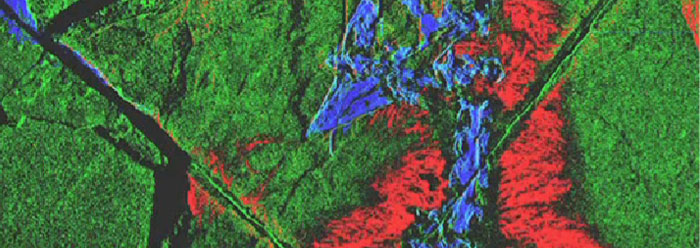

Analysis of the fossil's specific metals has yielded some spectacular results, confirming that the bird couldn't possibly have died millions of years ago. In a study appearing in Science, researchers used a new imaging technique to record the distribution of specific metal elements, like copper, across the surface of the fossil and compared that with modern feathers. Copper gives color to modern bird feathers and is held in place by carbon-rich organic molecules called melanins.

They found that the copper in extant feathers was in the same layout as the visible fossil feather outline and was highly concentrated right where they observed tiny barrel-shaped pigment-bearing structures called eumelanosomes.

To confirm that the copper was still integrated with the original organic melanin, the researchers used a scanning technique called XANES on three fossils, including C. sanctus. And indeed, the copper-melanin structures in the fossils resemble those of a living species of cuttlefish.1 In short, even after the more than 100 million years since the C. sanctus feathers and bones were supposedly buried, their molecular structures still match those of currently living creatures.

If this fossil is 120 million years old, its original copper and calcium should have, by virtue of the Second Law of Thermodynamics, leached out from the fossil into the surrounding rock layers.2 Instead, the scientists verified that almost no leaching has occurred.

In only half a million years, these very highly organized biomolecules would have completely broken apart, and their associated copper should now appear randomly distributed among the rocks, having naturally diffused into the surroundings. However, the original organic molecules have hardly decayed.

Overall, the study authors concluded that "the trace metal detail shown in Figure 1 is most likely derived from original eumelanin chelates [metal-holding molecules] in the feathers."1 Their use of the word "original" is significant, because it means that the fissile organic molecules had not been altered into more resistant chemicals. This means that the dead bird must have been fossilized in a recent catastrophe3 thousands—not millions—of years ago.

References

- Wogelius, R. A. et al. 2011. Trace Metals as Biomarkers for Eumelanin Pigment in the Fossil Record. Science. 333 (6049): 1622-1626.

- The Second Law describes the fact that matter and energy constantly tend toward disorder unless an external force organizes them. In a live bird, copper is well-ordered according to the pattern of its feathers. But after the bird's death, in time this order decreases, distributing and randomizing the copper. For more on the Second Law, see Thomas, B. Journal Censors 'Second Law' Paper Refuting Evolution. ICR News. Posted on icr.org June 20, 2011, accessed September 20, 2011.

- Fossilization requires a specific set of circumstances, such as the rapid burial that would occur during a catastrophic flood. For more information, see Fossils Show Rapid and Catastrophic Burial.

Image credit: Copyright © 2011 AAAS. Adapted for use in accordance with federal copyright (fair use doctrine) law. Usage by ICR does not imply endorsement of copyright holders.

* Mr. Thomas is Science Writer at the Institute for Creation Research.